HAPTIC INTENSITY

2018-08-09

The relationship between city and port was and undoubtedly still is the primary contributing factor towards the growth, development and overall apparent ‘success’ of the city-port. Significant progress in goods, human and information transportation coined with the inevitable need to go global in this day and age have brought about urban renewal with particular traits on port-cities. Like Olbia, such cities have “borne the full brunt of the consequences of these important ‘globalised’ and ‘globalising’ changes”1. Simultaneously Olbia has experienced dramatic alterations to its “building block materials”2 to such an extent that it has led to its intoxication.

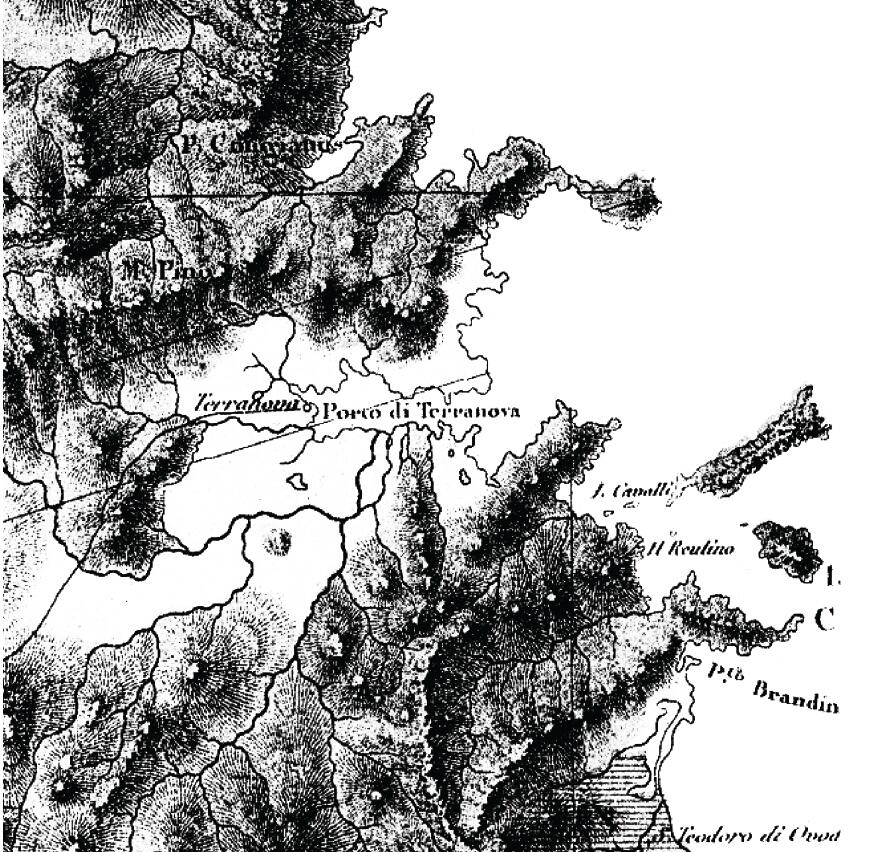

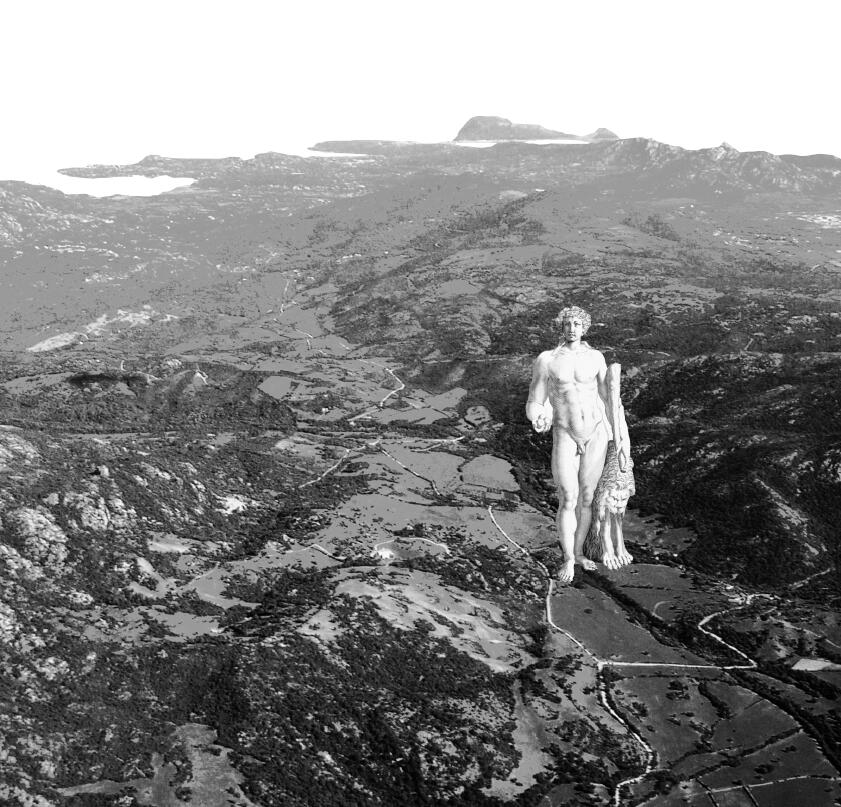

Situated in the northeast coast of Sardinia, Olbia (with Tempio) is the capital of the recently formed Olbia-Tempio Province. Having a beautiful natural setting on a plane by the Mediterranean coast, this port-city is surrounded by Gallura’s undulating landscape and boasts a uniquely rich cultural and historical heritage3. Olbia’s harbour history dates back to the Phoenicians. The gradual shift in occupancy brought about changes to the name of this ever-evolving harbour city. Following the island’s rule by the Byzantine Empire, Olbia was Sardinia’s capital and was known as Civita until Pisa founded a colony on the site and called it Terranova (Newfoundland). The name was retained until 1937, when Italy’s fascists were predetermined with recapturing past glory by re-christening towns with their ancient names. Thus Terranova returned to its

former Greek name Olbia4. Olbia has much to offer however the current situation does not pay tribute to the “magical harbour” D.H. Lawrence had portrayed it to be in 19215. Through its recent historic evolution, Olbia has undergone considerable pressure that altered its formation uncontrollably. This was particularly due to AGA Khan’s

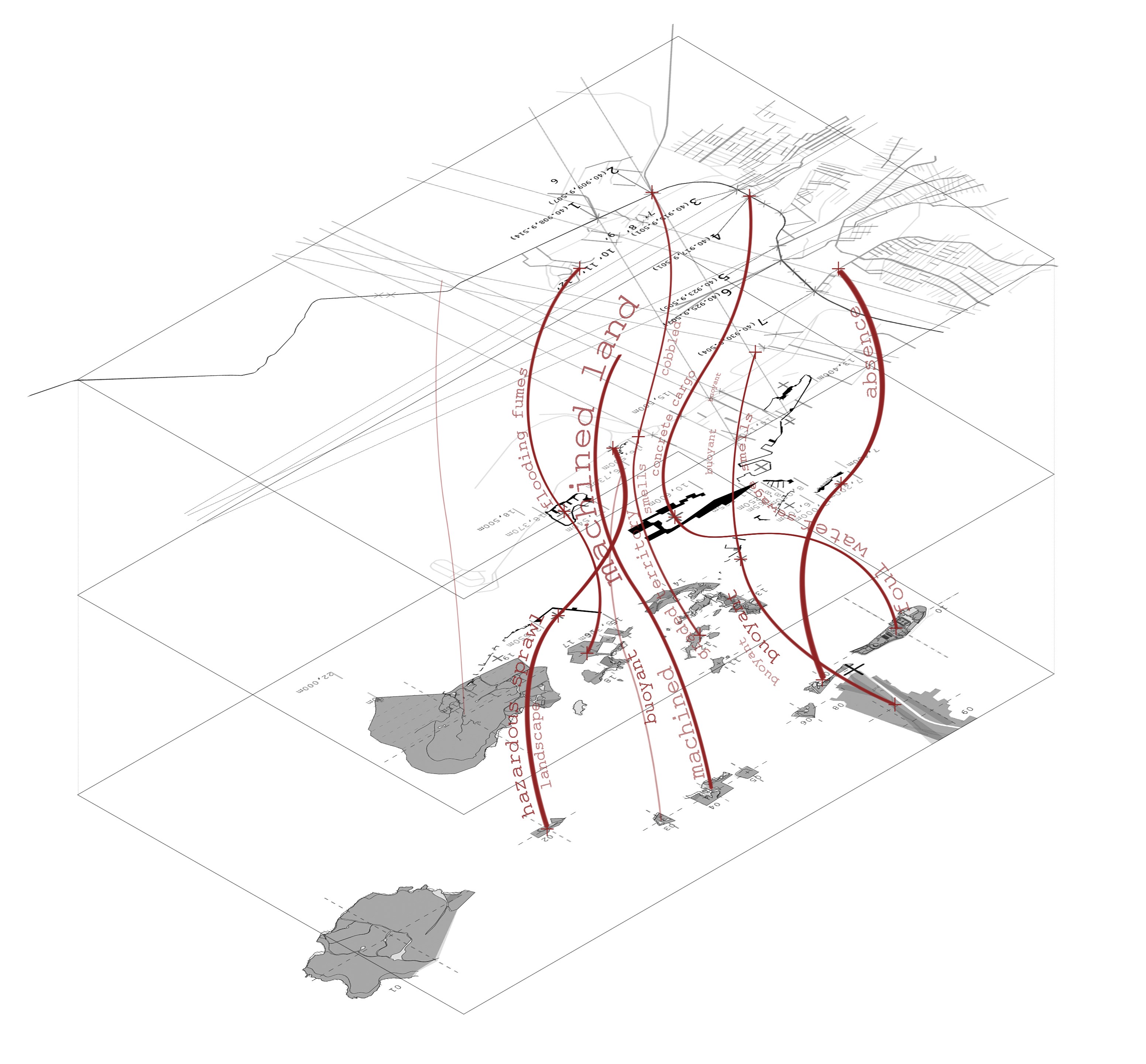

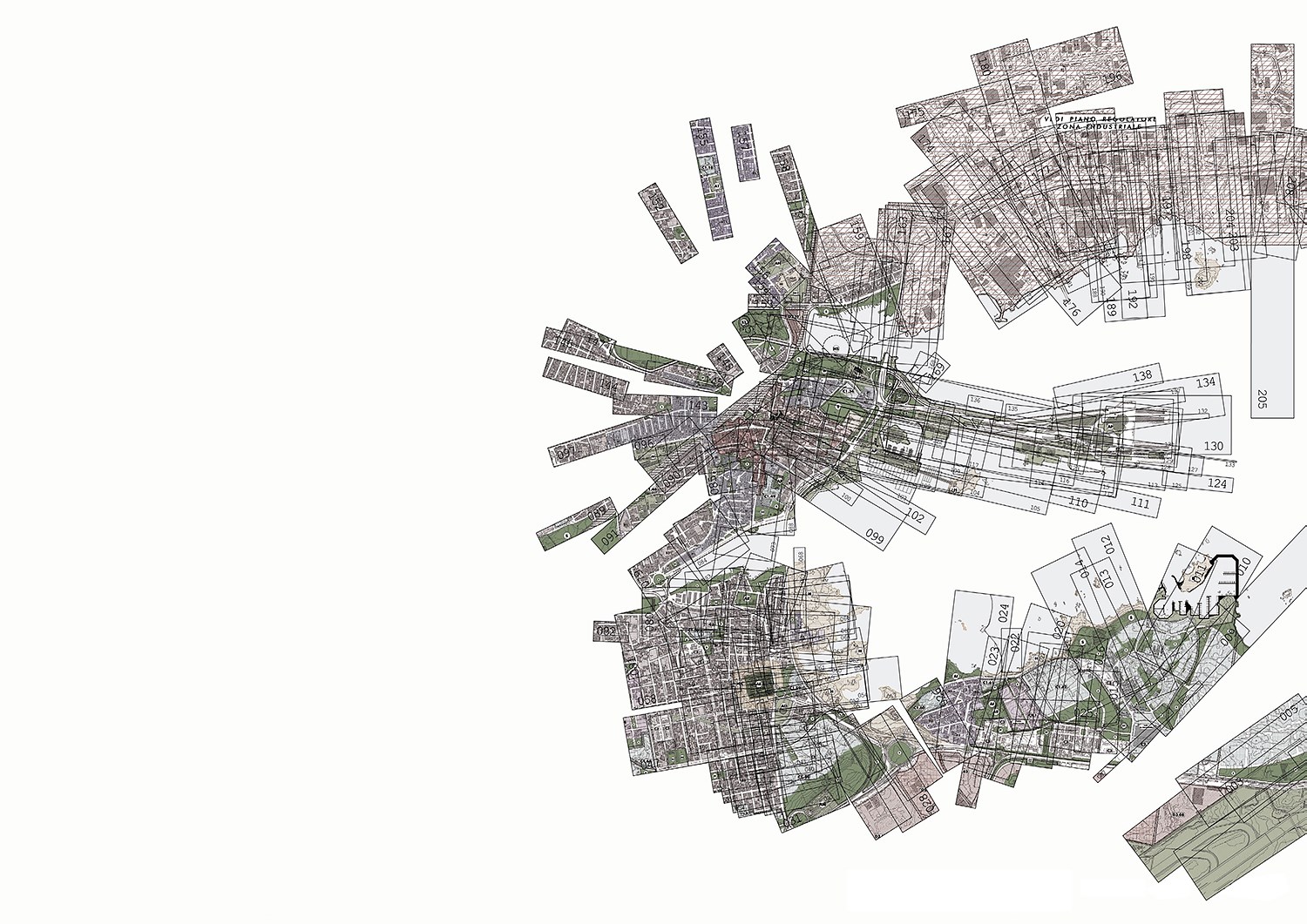

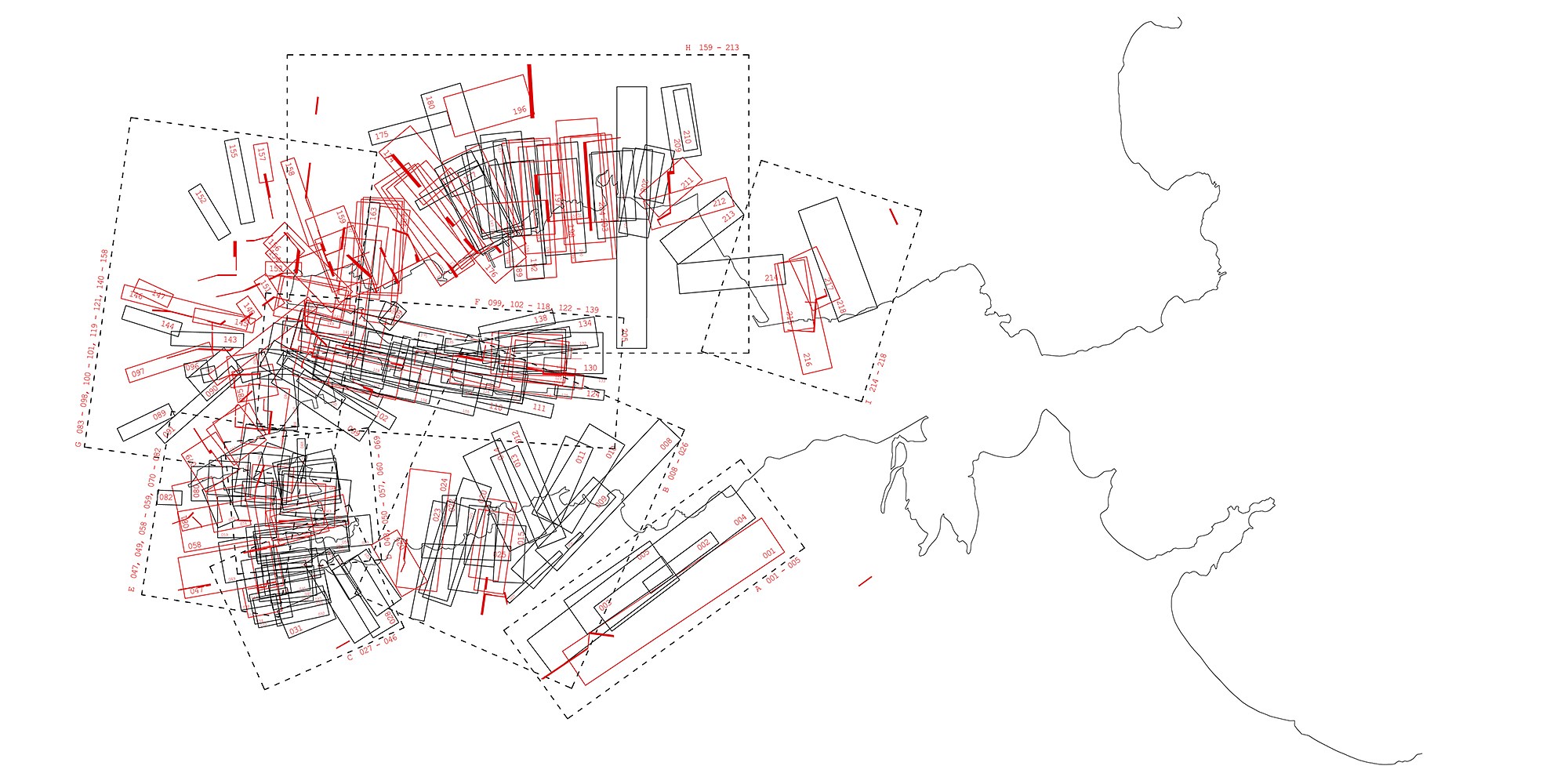

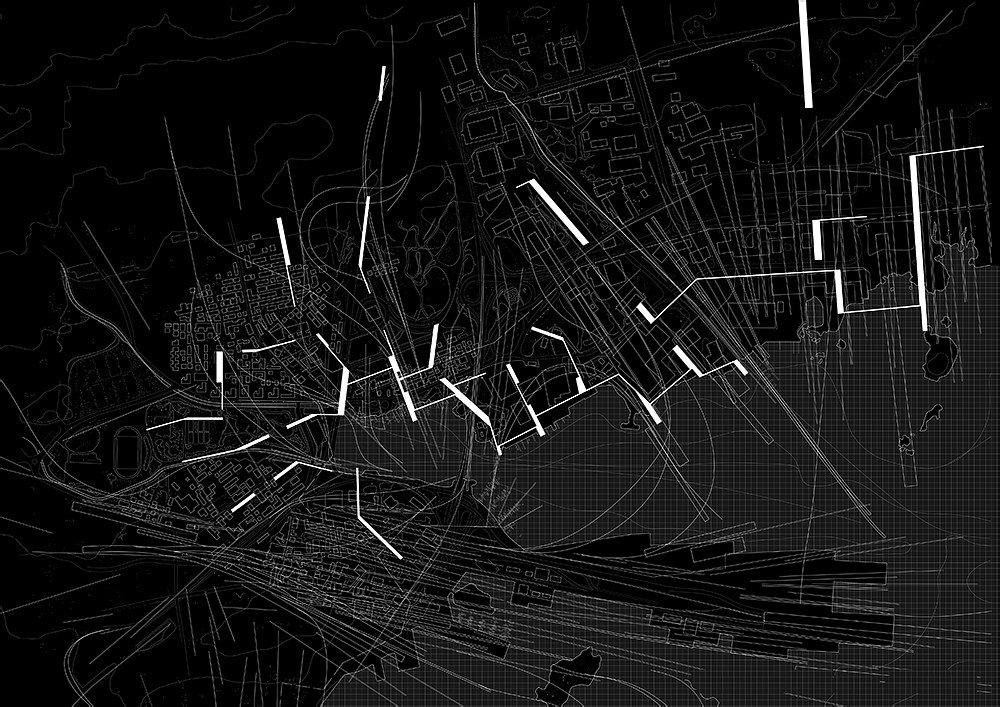

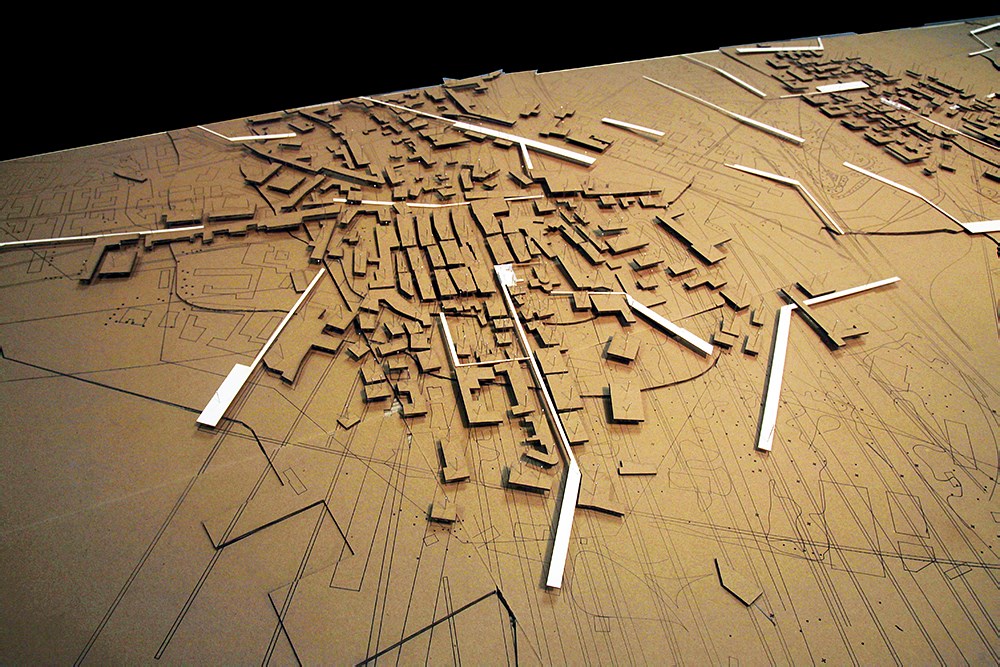

endeavor in the establishment of Costa Smeralda as a tourist destination and the sixties mentality that high industrial concentration was considered the way forward towards economic development6. Port activities have had a direct influence on the formation of urban organisms particularly in relation to the city’s layout with its natural setting and with the activities on the host city itself. Olbia is in fact a fragmented city, like other contemporary urban landscapes being “punched through by conduit landscapes of infrastructure”7 and isolated residential and industrialised capsules. The city is scarred by insensitive uncontrollable human interventions that seem to say to the city “I am here and I don’t give a damn”8. Not only does Olbia have one of the busiest ports of the island9, but unlike other port-cities, its airport is just within a few minutes from its centre10. This airport connects Olbia to major European cities11. A bus and train station directly connects the city to Sassari and beyond. While being bypassed completely, it is clear that Olbia serves as a transit city and a gateway to Sardinia and the rest of the world. The transient characteristic

emphasises temporality and hence the notion of continuous flux of overlapping energies that extend and intertwine, embedding temporal and spatial rhythm into the urban fabric12.

Amidst the presence of these imposing systems Olbia is a city that still has considerable potential for growth and development. With a population of 56,000 Olbiesi, the city occupies an area of 3761 square kilometers13. With the aim of transforming Olbia into a “true city of Europe”14, the city’s council has devised a strategy towards planning and directing the development of the territory over a long-term period. The challenge is to maintain a balance between the need for the city’s economic growth, ensured by maintaining connectivity and competitiveness with other cities, and on the other hand satisfying the city’s inhabitants’ needs towards higher urban quality standards. Claims that the ‘quality of life’ for cities on water is “to a large extent determined by what happens along their waterfronts”15, have brought about the ‘Waterfront Regeneration’ phenomenon. These interventions have played a vital role in the radica lmodernisation of cities’ urban layout. In some cases even the image of the city itself has been modified and the much-desired international recognition has also been achieved16. Not only is Olbia’s natural waterfront generally utilised for maritime purposes but further land has been reclaimed to satisfy demand. Any ‘unused’ areas that had the potential to spur similar regenerative effects have been squandered by empty car parking spaces, left dilapidated or unfinished due to failed business investments17. Amidst this dysfunctional edge, attempts to revive Olbia brought about Vanni Maciocco’s own National Archeological Museum on the ‘Isolotto di Peddone’, yet hardly any urban transformations have been noted.

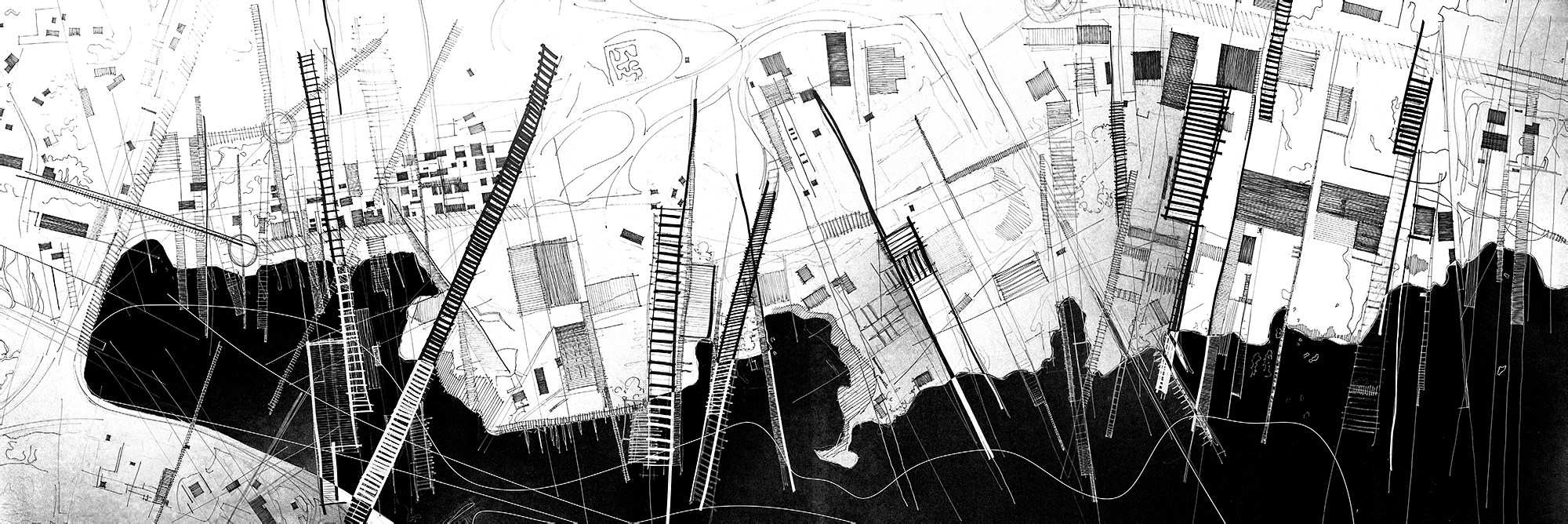

When it comes to the regeneration of cities, it is particularly evident that success stories do not merely focus on one particular building or area with the hope that this will have a catalytic economic and social effect on the rest of the city. After Bilbao’s success in 1997, a number of cities and smaller towns have succeeded in appointing star-architects with the hope that their large-scale cultural interventions would lead to “New Bilbaos”19. Such flagship projects might have a bearing on tourists’ destination choice but this does not necessarily imply that every large-scale intervention was or is beneficial towards the city to the same degree20. Frank Gehry himself insists that Bilbao’s success was and still is the result of a “conscious business decision” and a “big political commitment” on the city. When considering the rest of the surrounding interventions, Gehry stated that his museum is simply “a piece of the puzzle”21. Moreover, the transformation of city centres, waterfronts and historic areas into tourist-traps has the negative effect of instigating the migration of locals formerly based within the vicinity to the outskirts of the city. Areas boasting historic importance, vital towards the city’s identity are becoming capsuled spaces, either abandoned or commercially-tourist minded22. Castells argues that cities have transformed into everexpanding metropolitan zones whose limits are defined only by national borders. Rather than having one centre, cities now consist of a constellation of nodes linked through physical and virtual communication networks23. Perhaps what city officials do not realise when dealing with regenerative proposals is that rather than creating alienated capsules, they should not focus on the specific with scant attention to the context but their preoccupation should be dedicated to developing inclusive connected spaces. In other words a regional perspective should be implemented whereby awareness of existing conditions and activity should replace attempts of fresh development24. Interventions should attempt to blur immediate boundaries by infiltrating the urban organism.

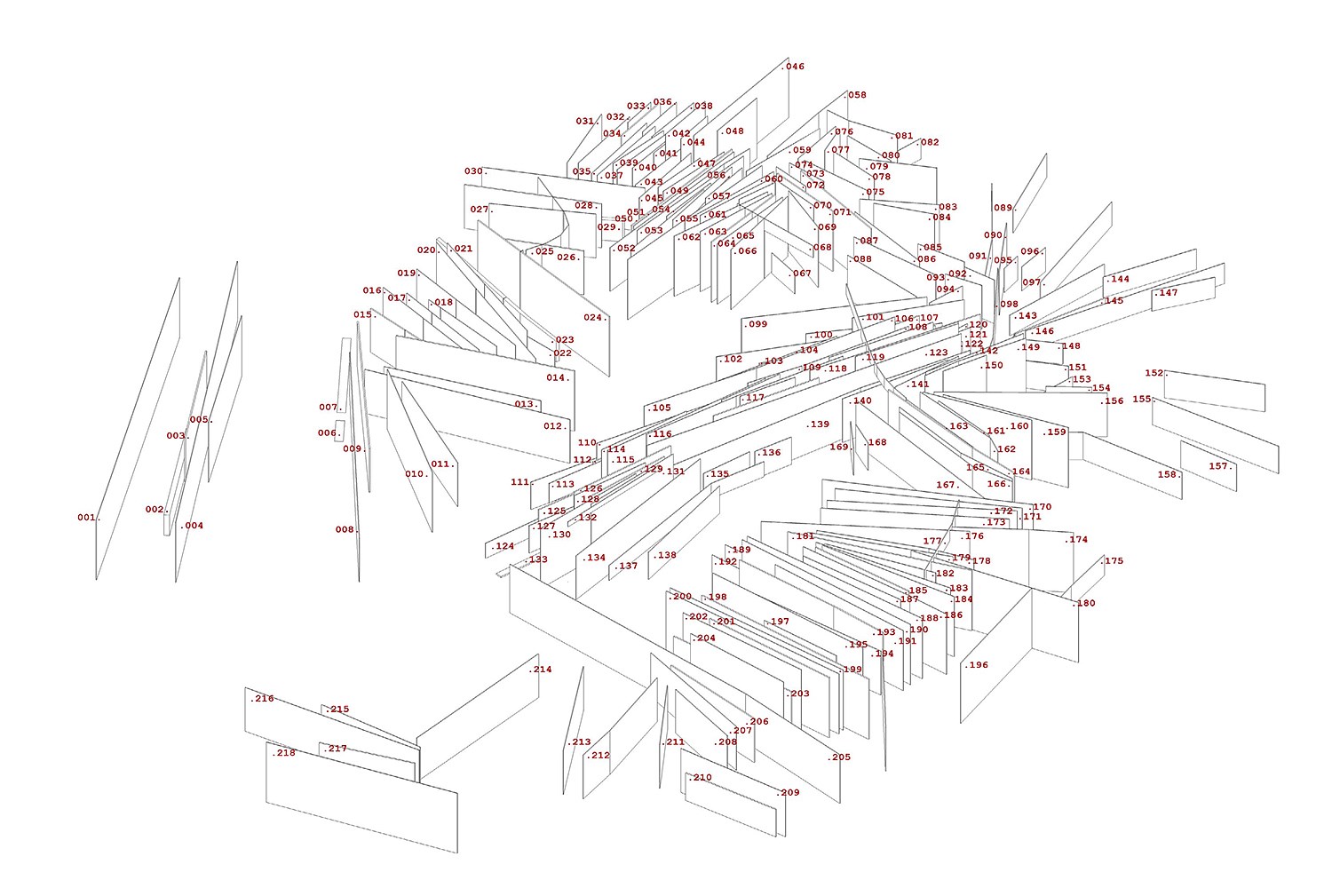

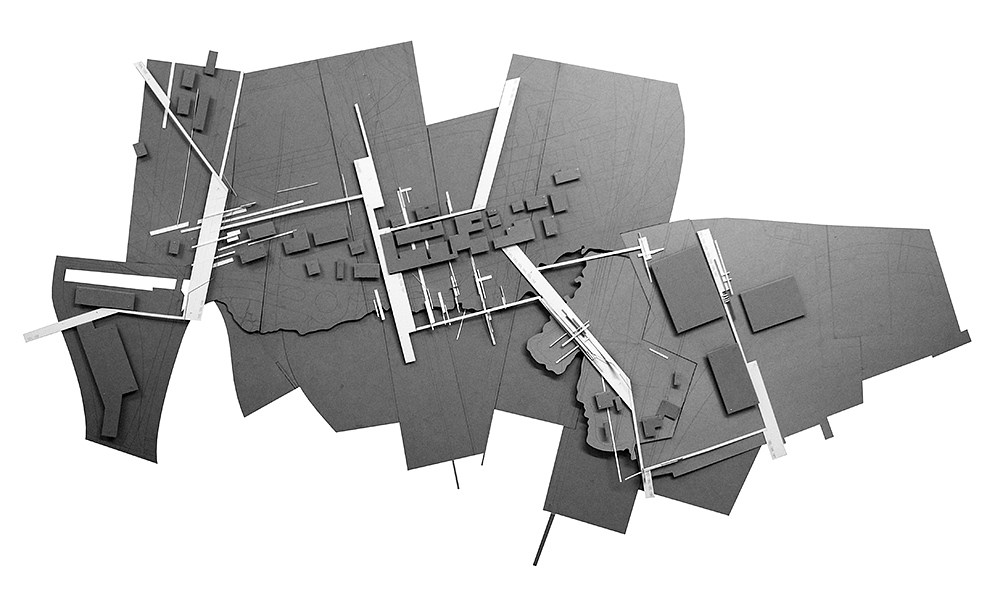

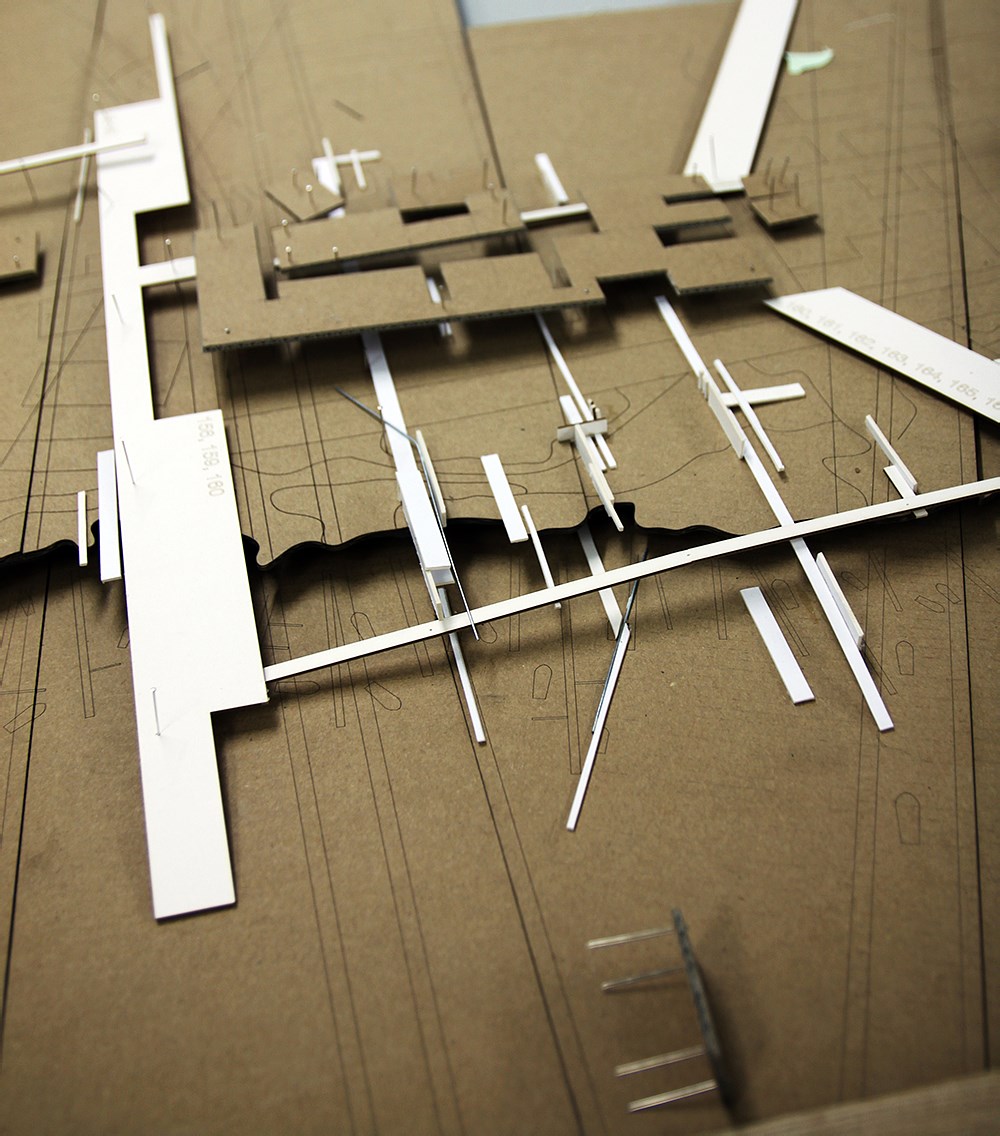

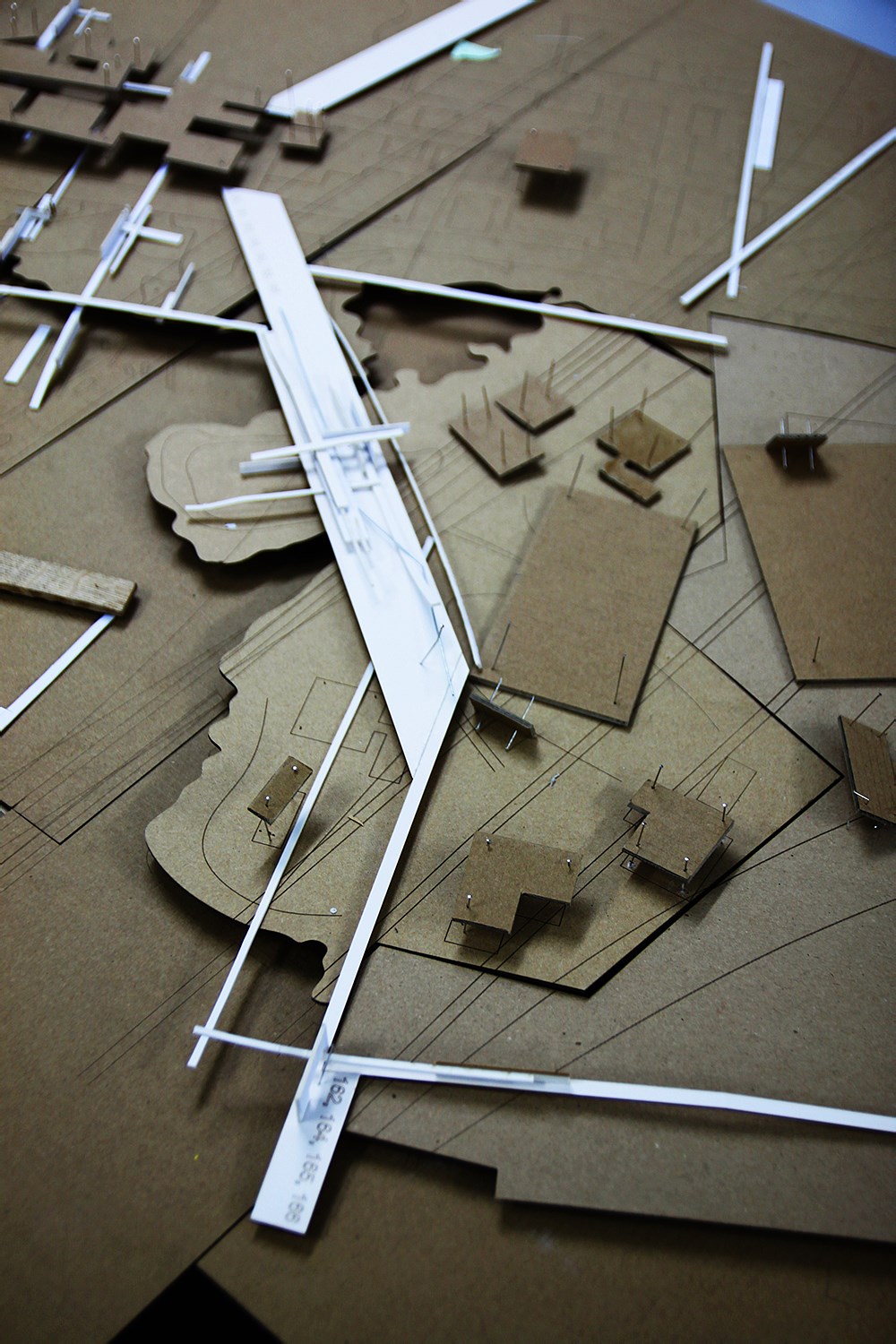

Although urban boundaries appear distinct, constant exchange occurs between them26. The identification of key sites within the city allows for the possibility of further bridging between systems whereby each is revealed to the other27. This may be achieved through a network or City Trail that is composed of a group of relationships, including a personal relationship with things that we know. Hence reference points along a city trail are essential for orientation, creating a flow with meaningful developments formed by specific context that changes along the same trail; interacting with existing building fabric, materials, social conditions and activity among other “form-giving factors”28. Architectural interventions are to take the role of “connective tissue”29. Architecture is thus no longer an autonomous entity, but connected to the city in its place and time30. In this manner it plays the important role of framing, distinguishing and mediating public and private space, while simultaneously blurring boundaries to create a greater sense of belonging within the city31. Manuel Castells makes a distinction between spaces of flow and spaces of place. Symbolic meaning is to be restored within the city through a conflation between proper urban design and architecture. However, given the crises of communication and the current trend to connect to the global, architecture has shifted its role from creating spaces of place to spaces of flow. Castells elaborates that “these are spaces of cultural archives, and meaningful exchange by the act of architecture”, cathedrals of information disconnected from the city at large32.

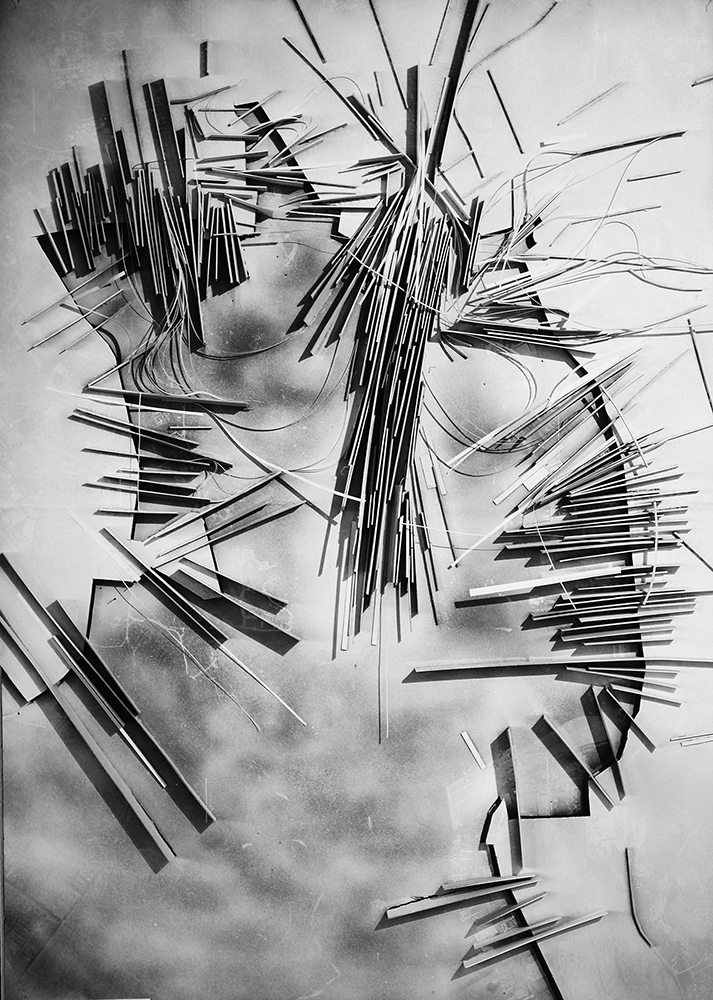

The public trail does not dictate a defined circulation route but allows for one to be seduced to wander freely, hinting a sense of depth and mystery while retaining a sense of composure. Scattered areas of shade, material variations and lighting intensities are experimented with to achieve a balance between composure and seduction. As architects enthusiastically gesticulate to describe their projects they tend to refer to the way they expect humans to interact and move through their projected spaces. The nodes along the trail are envisaged as spaces to be in and not simply to go through. They are to be “places that enliven, ensoul, ensocialize”that extend and connect to a continuum of stratified space of enhanced phenomenal transparency.

扫描二维码分享到微信